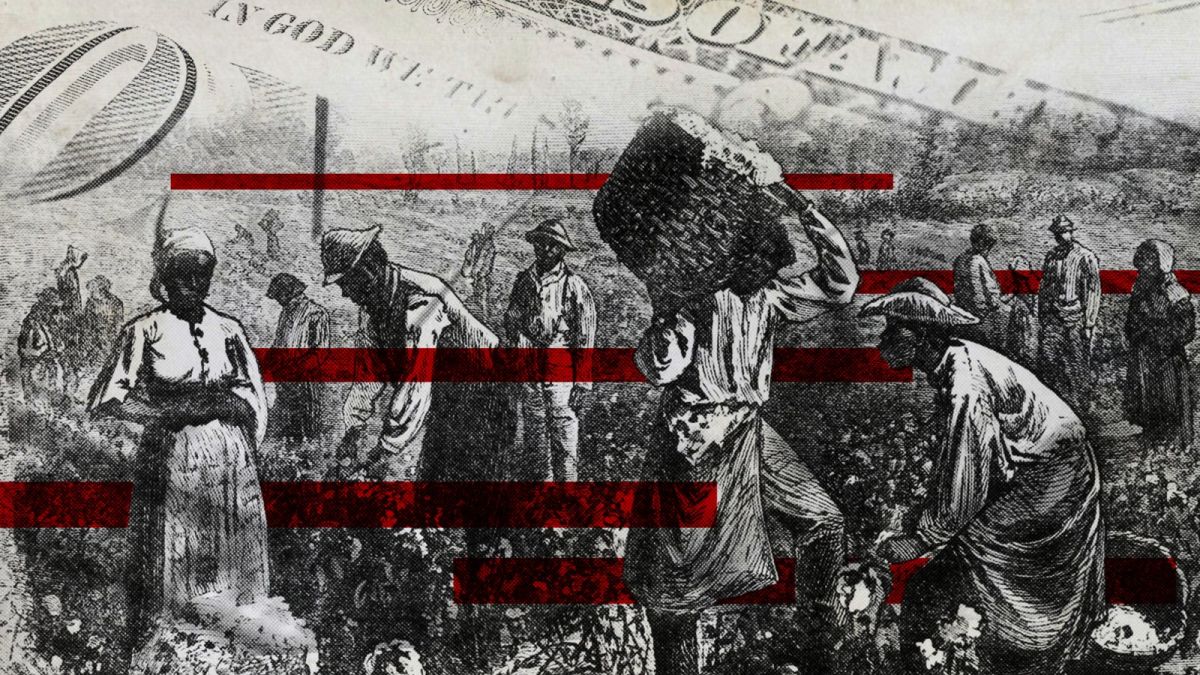

After the death of George Floyd, BET co-founder Robert Johnson argued that “now is the time” for the U.S. to pay $14 trillion in reparations to American descendants of African slaves. He’s right. But while the issue in the U.S. is seen largely as a domestic affair, international law creates an unequivocal basis for reparations.

The failure of successive U.S. governments to pay reparations paved the way for the Trump administration’s impunity. It has meant that the intergenerational trauma inflicted by the slave trade over centuries has never healed, but instead has been incorporated into many of America’s most vital institutions.

Some argue that because slavery was legal during much of the time it was practiced in the U.S., there can be no case for reparations. But the U.S. is bound by international law and must be guided by the precedent set by many other countries that have recognized reparations as a means to redress injustice.

Moreover, the prohibition against slavery has now achieved jus cogens—a peremptory norm, from which no derogation is permitted. This is the highest legal status in international law, and it means retroactive responsibility may be imposed on those who violated that norm. This is how the Nazis were prosecuted at Nuremberg: retroactively—for the jus cogens of crimes against humanity. On that basis alone, the U.S. may be held legally responsible for the historical enslavement of Africans and the consequences for their descendants.

Others argue that administering and paying reparations would be too impractical and burdensome. But reparations have been implemented in countries across the globe, whether due to genocide (Germany), forced labor (postwar Austria), racial discrimination (South Africa), civil war (Northern Ireland, Colombia) and illegal occupation (Iraq against Kuwait).

Reparations need not take the form of monetary payments and land restitution. They have been implemented through social programs, like home care in Germany for Holocaust survivors and educational programs and health-care services in Chile for victims of Augusto Pinochet’s purges. Even economically depressed countries, such as Argentina and Guatemala, have found the wherewithal to fund reparations programs. Why then should the U.S. be an exception?

This also defeats the argument that the cost of reparations can’t be imposed on society as a whole for a crime that a minority committed centuries ago. Across the globe, most taxpayers who have borne the cost of domestic reparations programs were not personally responsible for the crimes but did benefit from historical injustices. The lack of personal culpability can’t excuse inaction. The current protests are what happens when a society refuses to assume the responsibility of remedying injustice.

The case for reparations isn’t only a legal one. It is also about coming to terms with the historical injustices that explain continuing frustration and marginalization today. America can’t heal without acknowledging its “original sin”—slavery—and implementing a reparations program that encompasses truth, reconciliation, atonement and compensation.

The grim legacy of slavery is a form of structural racism that continues to bar social, economic, political and health equality for many African-Americans. That is itself a justification for reparations.

Another is that more than half a century since the end of Jim Crow, innocent African-Americans continue to be murdered at the hands of police officers and vigilantes—apparently with impunity, unless it is caught on video. There can no longer be any question that the legacy of slavery will endure unless reparations are made as a first step toward corrective justice.

Mr. Ali is a partner at a global law firm. He served as a section chief for the commission that dealt with the reparations claims arising out of Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait.